Train Dreams Offers a Quiet Breath

Some films are undeniably of their time. They speak to their moment with a loud, clear tone. This year is rife with commendable examples of such films: Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (topping many year end lists and racking up critical awards), Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just an Accident. We need movies like these to challenge us, to discomfort us, to make us interrogate the cultural and social environments we find ourselves in, to hunger for change.

But we also need movies that feel, for lack of a better word, timeless. These are not distractions or escapes from the woes of contemporary life; instead, they allow us to step back and view life from a separate perspective. While they don’t provide a clarion call for this present moment, they nevertheless offer wisdom with a still, small voice.

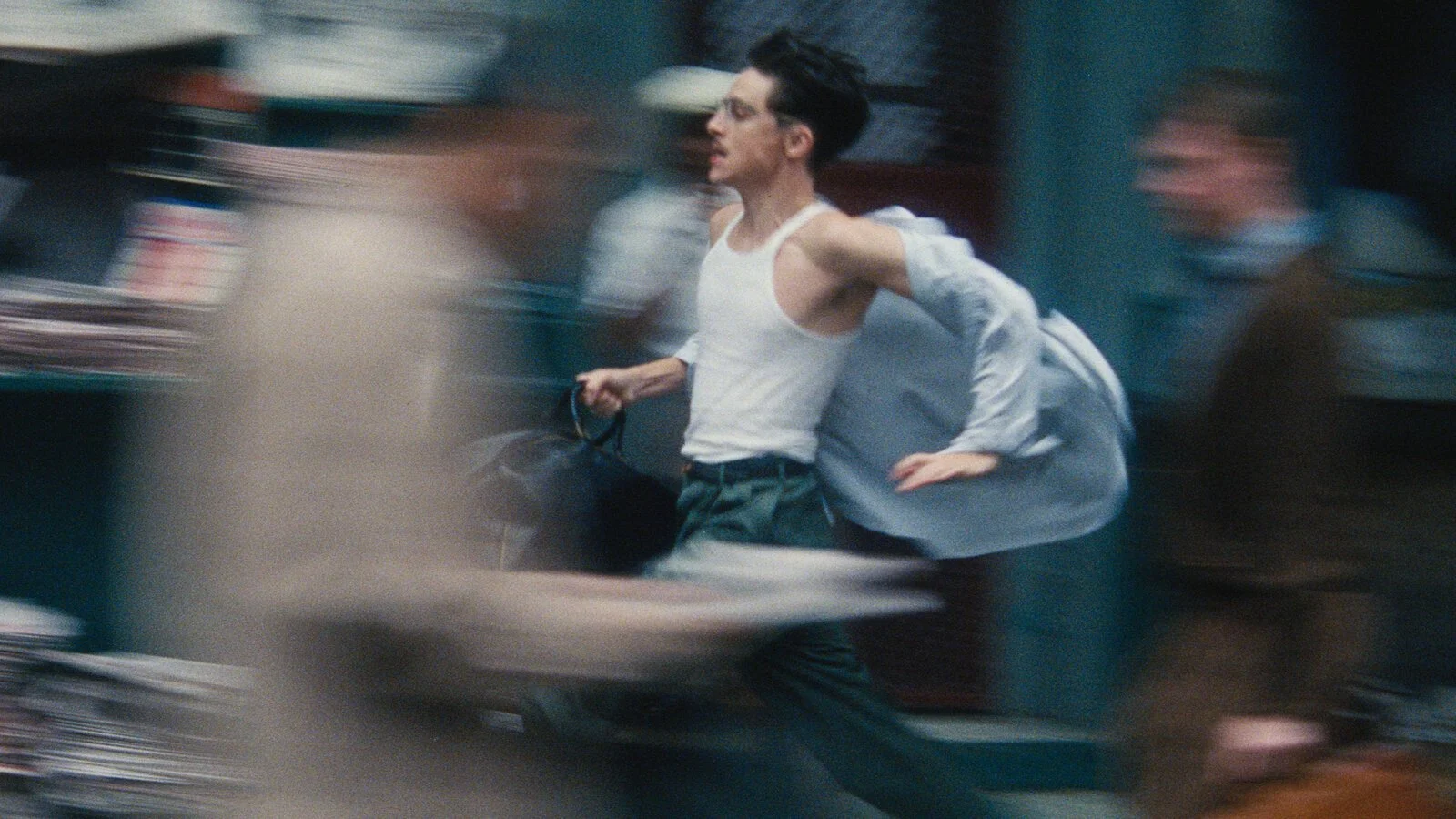

Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams is one such film, and it’s one of the best movies of the year. Bentley adapts Denis Johnson’s 2011 novella, a brief, pensive reflection on the fading of the American West, into a cinematic tone poem meditating on the persistent questions of life, death, and the changing tides of time. Robert Grainier’s (Joel Edgerton) life spans from the late 1800s to 1960s, and locates him in the Pacific Northwest of Idaho and Washington. Orphaned at a young age, he drops out of school early to work for an income, primarily through logging and building railroads. The flow of Train Dreams is more poetic than narrative: images recur, foreshadowing and reflecting at will, as Will Patton narrates the arc of Grainier’s life.

Edgerton is an apposite choice for the film, bringing a believable physicality and slight restraint to his facial expressions. But the real enjoyment is in the supporting cast. Patton’s voice is a sonorous and rhythmic guide, a faithful companion as we travel this transforming world. Paul Schneider shows up as a wandering logger who never slows in his verbal processing of holy scripture. Felicity Jones’ part as Grainier’s wife, Gladys, is fairly thin—I could see critiques of either her performance or the story’s role for her character. She’s capable of what the movie asks, but the role lists toward unfortunate tropes. No one, however, is anywhere near as memorable as William H. Macy as Arn Peeples. Peeples is one of the other “itinerant men” that Grainier finds again and again on various jobs. While Grainier’s tools of comfort are axe and saw, Peeples is an explosives expert. Where Grainier is taciturn, Peeples is poetic, even prophetic: cutting down a tree “upsets a man’s soul whether he recognizes it or not.” Macy gives the wisdom a comfortable, weary quality—he’s settled into this world for all its aches and sadness.

As Grainier’s life is (gently, subtly) transformed by these relationships, so the landscape, the whole world around him, is changed as well. For Train Dreams is small in scope but casts its eyes wide toward much broader concerns. The narration briefly notes that the bridge that Grainier spent so much labor cutting down trees to build will only be replaced by a newer one made of steel and concrete. It’s a quick aside that reveals, in microcosm, the endless engine of industry and the way it scars the landscape. Grainier’s labor wearies him, but it’s soon made moot, overrun by the pace of technology. The regions of Idaho and eastern Washington he inhabits find their woodlands depleted further and further each year. The human endeavor and its resultant tragedies is only one side to the story, though. Nature, too, is prone to destruction, whether by thunderstorm or flood or wildfire. Tragedy, as it does with all lives eventually, strikes close to Grainier.

There’s rightful comparisons to the work of Terrence Malick to be found in Bentley’s film (and scattered throughout reviews), but it’s worth understanding the distinctions. The narration here is not the interior whispers or prayers of the protagonist—Patton’s descriptions are distanced, often focusing more on context and actions than Grainier’s mental or emotional state. We are not brought into his interiority; we witness his actions, interpret his emotion through gestures and expressions. This may sound like arguing minutiae, but it creates a significant difference for how we relate to the protagonist. The technique sets us slightly apart from Grainier, and we are asked to do more work to meditate on the film’s ideas. Bentley is working in his own mode, making use of (some of) the tools that Malick has sharpened. Certainly the last fifteen years have seen many indie films heavily—at times wholly—reliant on Malick’s style, but Train Dreams distinguishes itself.

This goes for the cinematography, too. It’s too easy to categorize an emphasis on nature photography as Malickian without attending to other components of technique. (Can no movie be enthralled by nature without living under Malick’s shadow ever again?) Working with cinematographer Adolpho Veloso, Bentley employs calmer, frequently static frames and methodical zooms to express this world. Handheld camerawork is used, but with enough restraint to give the film its own sense. This is not the rush of inspiration of The Tree of Life, but the slow breath of a moment’s pause.

The intent of Train Dreams is an invitation: share Grainier’s world for a time, witness his life, and consider all life. Grainier changes. America changes. The world changes. In some ways that are good, in some that are regretful. Regardless, it all matters. As Arn Peeples says, “this world is intricately stitched together.” Even the forgotten life leaves its mark. On others, on the landscape. Grainier’s life passes quietly by worldly standards. But Train Dreams reverberates it with beauty and wonder.