Linklater Makes the New Wave His Own in Nouvelle Vague

Time passes inevitably and methodically, taking everything along with it. Everything fades. All things go the way of all the earth, even that which once seemed no new and vital. Even revolutions settle in as chapters for history textbooks. The radical becomes familiar, the familiar becomes commonplace, the commonplace becomes dismissed.

At the start of 1959, Jean-Luc Godard was merely a film critic for the Cahiers du Cinema, not a director. He had aspirations—of that there is no doubt—but he was restrained to discussing films, not creating anything of his own. That would soon change, and the result would be a revolution for cinema. His debut feature, À Bout de Souffle (Breathless), became the clarion call of the French New Wave (even if many of his Cahiers compatriots had already helmed features). Movies would never be the same, although movies would adapt and glean from the inheritance of Godard’s work.

The making of Breathless is the subject of Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, following from the initial funding of the film to the first screening among Godard’s closest friends. Linklater (School of Rock, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise) has been directing films for over thirty years, and 2025 finds him in a wistful, reflective mode. In addition to Nouvelle Vague, the recently released Blue Moon takes place immediately after the opening night of the musical Oklahoma! Linklater has always been known for films and characters that wear their heart on their sleeves, and he’s showing his own through these meditations on what makes great art and the personalities it takes to achieve that (or at least attempt to do so).

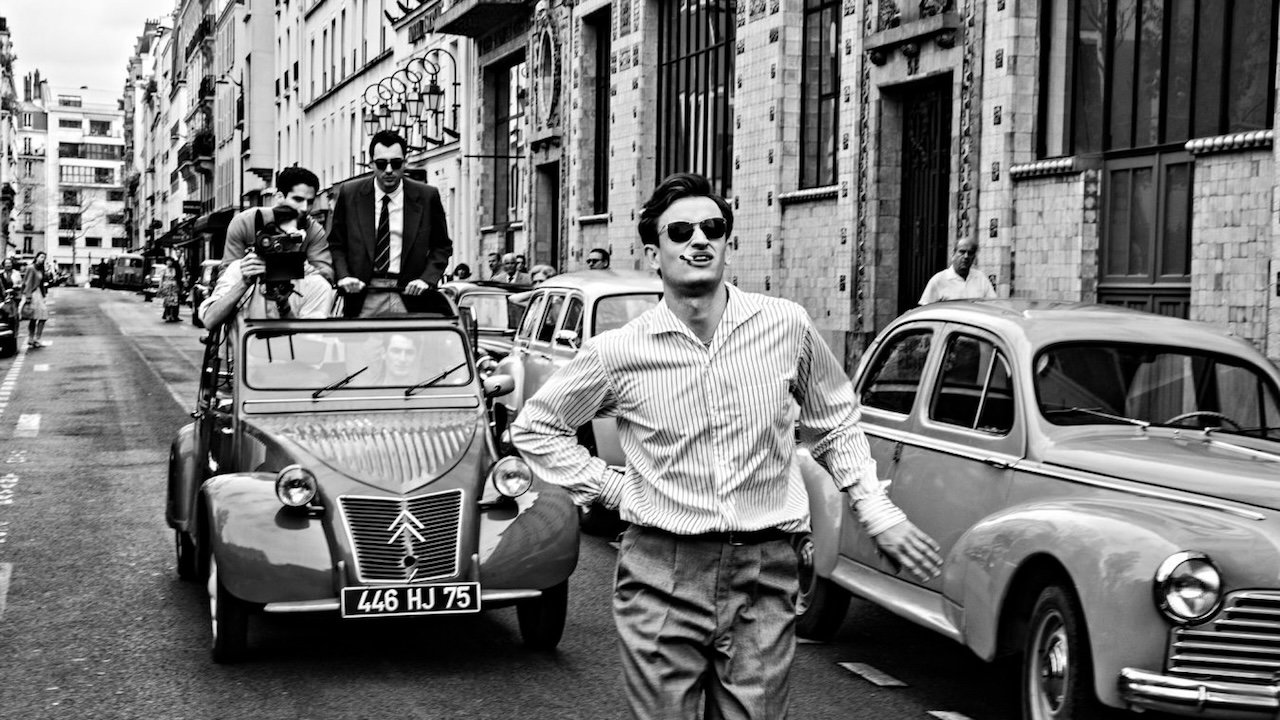

Nouvelle Vague is not a biopic, and it persistently avoids hagiography and simple glorification—certain temptations when dealing with the lofty idols of Godard and Breathless. As he’s occasionally inclined toward, Linklater fills the cast mostly with inexperienced or unknown actors: Guillaume Marbeck, a French photographer, fills the director’s shoes; Aubry Dullin takes on the steep task of portraying the idiosyncratic Jean-Paul Belmondo; Benjamin Cléry plays assistant director Pierre Rissient. The most well known name among the cast is Zoey Deutch (Juror #2, Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!!), portraying Jean Seberg, the American actor whose legacy would become closely tied to the film.

Marbeck is the standout—he reveals the sui generis revolutionary in Godard, while also making it clear that he must have been insufferable at dinner parties. Most conversations are asymmetric, as Godard interrupts with emphatic declarations of the right and wrong way to make a film—frequently to the frustrations of cast and crew—prompting Seberg to ask at one point, “Are you making up how to direct as you go along?” Dullin and Deutch are weaker in their roles, but they are also up against the challenge of embodying singular, beloved personalities. But there’s a great deal of fun found among the film’s crew, particularly Clery’s playful (if ahistorical) take on Rissient and Matthieu Penchinat’s depiction of cinematographer Roaul Coutard.

The aim for Godard is to press into the unfilmable. He’s advised by other directors along the way: his friends Truffaut and Chabrol, but also Jean-Pierre Melville (who appears in Breathless), Roberto Rossellini, and Robert Bresson. “There’s no technique to capture reality.” Hard to capture it, harder to break it. The script, along with Marbeck’s performance, brings enough artistic doubt to protect this from becoming a sugarcoated affair. Marbeck is bristly, aloof at times and inexhaustibly animated at others.

Once filming begins, the crew realize that Godard’s going to spend more time talking than actually preparing or shooting scenes, and Nouvelle Vague becomes just as infused with Linklater’s spirit as Godard’s ghost. This is a group of young people itching to create, to shatter conceptions of art, to prove their worth to the world but never on the world’s terms, and to play some pinball. They aren’t far afield of Ethan Hawke’s Jesse, the teenagers of Dazed and Confused, or the Austinites of Slacker. Godard’s troupe fits right in with the gadabout artists and habitual philosophizers that Linklater has always been interested in. It also gives the film a laidback vibe that allows it to quietly decompress the tension of creating a movie about one of the most cherished movies of all time.

If you want to, you’ll learn a bit from Nouvelle Vague, but the main draw is to immerse yourself within this crowd in this time and place. Filmed with gorgeous lighting of Parisian streets, with wise (and restrained) nods to the camera and editing techniques that made Breathless so radical, Nouvelle Vague maintains an impeccable atmosphere. Revisit Dazed and Confused to envision life in the youthful 1970s, and sit down with Nouvelle Vague to imagine yourself in the artist cafes of 1950s Paris.

Linklater has crafted a film that is as much his own as Godard’s, which is an achievement. Nouvelle Vague is not a hagiography, nor is it a paint-by-numbers exercise. If the former is the typical Scylla, the latter is the Charybdis that exists only to remind the audience of a much better film they could be watching. Linklater navigates his way through both, inviting us into a world of artistic drive, youthful meandering, and above all enjoyment.