Ethan Hawke Gives a Sad, Stunning Performance in Blue Moon

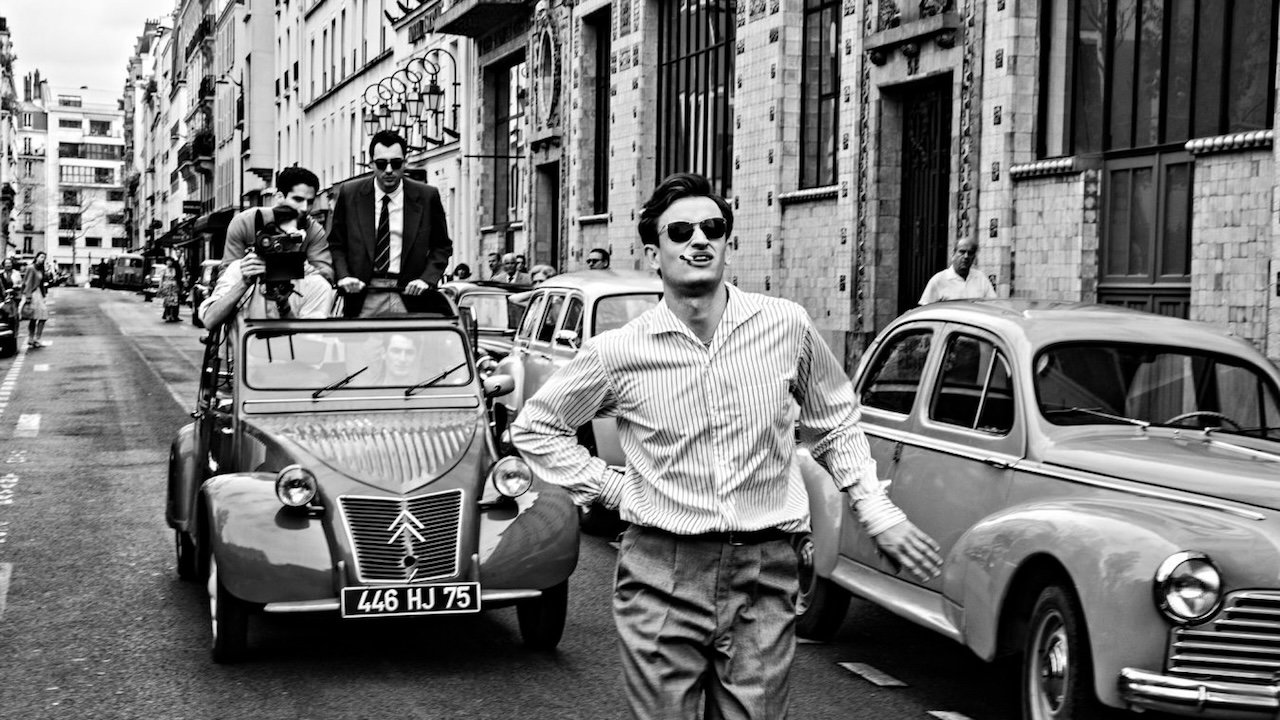

With Nouvelle Vague (also released this year, centering on the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless), Richard Linklater provided a reminder of his dexterity for capturing the energy and frustrations of youthful artists. In Blue Moon, he juxtaposes that (with, perhaps, even greater skill) by depicting the sour desperation of an aged artist watching the last bit of his career dissipate. In the former, Linklater forms his cast largely from new or unknown actors; in Blue Moon, he reunites with Ethan Hawke, who has starred in Linklater’s Before trilogy and Boyhood. The pair of films creates a fitting symbol for Linklater’s career: comfortable with inexperience, appreciative of improvisation, but also able to become “buttoned up,” working with a more refined script and acting method. His directorial capacity creates a space for performers on either end of that spectrum and allows him to turn his attention to hesitant fledglings (Dazed and Confused, Boyhood, Everybody Wants Some!!), uncertain reality (A Scanner Darkly, Waking Life), tentative romance (the Before trilogy), and totemic works of entertainment (in this pair of films).

If Nouvelle Vague immerses us in the thrill of midcentury Paris, Blue Moon immerses us in a scene we may not want to enter. Hawke portrays (or better: embodies, succumbs to) Lorenz Hart, the songwriting partner of composer Richard Rodgers. Together the two created renowned songs such as “Manhattan” and “The Blue Moon” for the theater, and they enjoyed substantial success, but their collaboration waned as Hart’s alcoholism worsened. Rodgers partnered with Oscar Hammerstein II, and their first collaboration, Oklahoma!, became a blockbuster, launching the pair into the stratosphere of American theater, leaving Hart behind.

This is where Blue Moon picks up and concludes, in Sardi’s restaurant just after the Broadway premiere of Oklahoma! But we are not here for Rodgers or for Hammerstein. We’re here for Hart, sitting with him at the bar as he works through the five stages of grief and tosses a few new ones in for good measure. Hart is not the easiest man to get along with. He’s plagued by bitterness and he knows it. He’s also adamant about his peculiar artistic tastes—this is a man who insists that the best part of Casablanca is Claude Rains (as though Peter Lorre never even existed). And everyone within earshot is fated to hear his incessant diatribes about lazy rhymes, hack dialogue, and transcendent beauty. Blue Moon is a claustrophobic movie in scope, form, and idea. Apart from a momentary prelude, the image never departs the walls of this bar. The script allots a staggering percentage of the lines to Hawke’s Hart—despite constantly talking to everyone around him, Hart rarely allows them a breath to respond. These decisions also trap us in Hart’s emotional space, forcing us to receive and confront his frustrations. It’s a single set movie and is nearly a one man show. But what a show it is.

Hawke is, to say it simply, remarkable. This is one of those rare times where you realize halfway through the movie’s runtime that you’re likely watching the best starring performance of the year. This is Hawke—an actor so often relaxed and inviting—at his most shivery and hunched, hardly looking or sounding like the man we know. His characteristic charm is fully curdled in Hart, all jealousy and artistic anger. At one point Hart praises the perfect lyric or sentence as enabling levitation, a moment that “breaks free from gravity.” Well, Hawke’s performance reaches that level of wonder, but it would be impossible to see Hart as levitating; he’s always at risk of slumping into a puddle on the floor of the bar. Hawke never once slows down, but he’s never repetitive. This is a fine work of scriptwriting as much as performance, composing a portrait of an artist whom time, taste, and everyone else is leaving behind.

Come for Hawke’s performance, stay for Hawke’s performance. But that’s not to say he leaves the only strong impression. Margaret Qualley plays Elizabeth Weiland, Hart’s protege and object of his obsessive affection. Qualley has a far quicker energy than anyone else here, and it’s effective in expressing the gulf between her youth and Hart’s waning verve. Hart directs most of his odes and barbs at the bartender, Eddie (Bobby Cannavale), and pianist Morty (Jonah Lees), and both of them slip in decent laughs and annoyances as they react. More exemplary are Andrew Scott as Rodgers and Patrick Kennedy as E.B. White. They both have less screentime, but they know just how to use it. Scott (Wake Up Dead Man, All of Us Strangers) is a flexible performer, but he approaches this with a physical pragmatism. His Rodgers is guarded, restrained in a way that enforces a physical distancing between himself and Hart. He presses back with real ire, making clear the difficulty of decades dealing with all of this. But it’s Kennedy as E.B. White that I’m thinking about most, joining Benicio del Toro’s turn in One Battle After Another and William H. Macy in Train Dreams to form a 2025 triumvirate of brief supporting performances that present themselves as small, crucial gifts. White is calm, patient, and obliging, calling for a quiet performance that nonetheless exudes an immensity of grace and kindness.

While Blue Moon and Nouvelle Vague are drastically separated in tone and form, there is a common thread connecting them. In Linklater’s vision, Hart is an artist trying to pin down enchantment, trying to articulate the ineffable despite the impossibility. What separates Godard and Hart most in these movies is not their aim—they are kin in their artistic passion—but their impending success or, in Hart’s case, lack thereof. Blue Moon is not an “enjoyable” film, forcing us to sit with Hart’s neediness, but there’s something very human unveiled as he rails against the dying of his spotlight. He’s facing failure and flailing, and he fixates on anything else he can. But he can’t deny the force of his longing or his sadness. “Who’s ever been loved half enough?” We’re all suckers for other people’s love and admiration and approval. Hart just no longer has the words to hide it.