Wake Up Dead Man, or “Whose Body? Broken For You”

There are a thousand variations on murder mysteries, but they all begin with a shared question: to pull from Dorothy Sayers, “Whose body?” Even before wondering who put that body there and for what purposes, we must first meet the victim with the blade in their back. Rian Johnson, now on his third Knives Out mystery, is playful and winking about his familiarity with the genre. In fact, Sayer’s Whose Body? shows up on a rather savage book club list alongside other mystery writers such as John Dickson Carr, the king (or at least greatest dissector) of the locked room murder plot.

Our victim in Wake Up Dead Man is Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin), the leader of the small, if devout, crowd that gathers each week at Our Lady at Perpetual Fortitude to hear his sermons. Although perpetual indignation may be more what they receive, as Wicks’ sermons often veer toward fiery political rants which resemble fringe podcasts or social media ravings more than any exposition of scripture. But that’s exactly what his flock is searching for—or what they’ve been shaped to desire. Glenn Close plays Martha, the longest tenured church member, whose frigid, haughty sense of faith fits hand-in-hand with Wicks’ wrath. Kerry Washington’s Vera has also been around since childhood when she attended with her father, and she now brings her adopted son, Cy (Daryl McCormack), along with her. Newer members include Dr. Nat (Jeremy Renner, no hot sauce in sight), who struggles with substance abuse and loneliness; Lee (Andrew Scott), a sci-fi writer losing his grip on his own once-devoted followers; and Simone (Cailee Spaeny), a cellist desperately looking for healing.

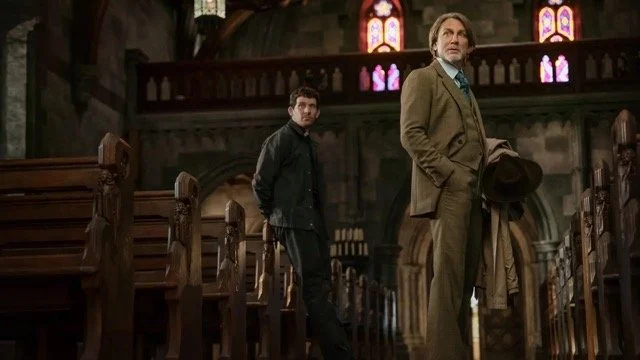

When Wicks drops dead in the middle of a service, suspicion could be directed at any of them. Or at Rev. Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor), the young priest who’s been assigned (read: disciplined) to join Our Lady as Wicks’ new assistant. It’s not long, of course, before the famed detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) arrives to offer his services and satisfy his insatiable curiosity regarding murder.

For those familiar with Johnson’s previous entries, you know that the blade in Wicks’ back isn’t the only one being wielded. With each movie, Johnson has turned a blade toward a different societal moral failing. The first Knives Out questioned the poison of wealth and how it becomes a cancerous influence inside the hearts of those greedy for it. Glass Onion shattered the heroic myths of tech guru and influencer culture (America’s new money, in a sense). And now we find our latest characters in a cathedral.

Johnson is not here to carve into the church or religion, however, as much as the hateful rot that’s corrupting it. Wicks is volatile and feeds on the hurt responses of those he provokes, those he pushes away from his church, all the while reaffirming the true faith of those who continue to follow him. Father Jud arrives on the scene as his antithesis. When Wicks tells Jud that “the world is a wolf,” Jud immediately pushes back with a simple, emphatic, “no.” What Wake Up Dead Man is asking underneath its mystery is: What should the posture of the church be? Fists up and ready to fight, or open arms?

This approach shifts the balance of Wake Up Dead Man compared to Knives Out and Glass Onion, even going so far as to make O’Connor the clear lead above Craig’s Blanc. Johnson—who grew up in the church, though he describes himself now as nonreligious—attends to religion thoughtfully. I mean, this is a movie that takes the time to pray. Whereas Johnson seemed ready to demolish the entire institutions enabling “old” wealth and tech overlords in the previous movies, Wake Up Dead Man doesn’t indicate that he wishes to tear down (deconstruct, anyone?) the church. Instead, he wishes to purge it of the political idolatry that has co-opted its worship. Too many of the words out of Wicks’ mouth come straight from soundbites; but Jud so often delivers a statement that is succinct, accurate, and undeniable in its distillation of biblical ideas. I’m not sure O’Connor can give a bad performance (he’s also remarkable in this year’s The Mastermind), and he brings an impassioned warmth to Jud.

The actual mystery here is not quite as thrilling or puzzling this time around; while there are still unexpected twists, there’s also enough clear (and occasionally clever) foreshadowing of future story beats that you can settle in and wait for those to occur. The supporting cast also isn’t given as much characterization. Spaeny and Scott are the standouts, but Close lays the brimstone on a bit too thick, and others merely register as sketches. The heart of this film remains with O’Connor and Craig, their divergent beliefs (Blanc is an adamant atheist) set aside for their common goal of solving this murder.

Weighty matters aside, the setting of this story also affords a chance for Johnson to let some freakier influences shine through—as the story turns darker, Wake Up Dead Man briefly becomes an all-out gothic horror, replete with late night chases through forests and acid baths. It’s possible that Johnson has never had as much fun lighting a film as with this one. He picks up the stained glass motif to wash the scenes in variegated spectrums, at times expressing the full emotional arc of scenes through lighting changes. A rainbow of color deadens to musky darkness, only for grey light to suffuse the cathedral in a haze that recalls the stark beauty of Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light. It’s a blast just to watch what Johnson and cinematographer Steve Yedlin come up with, like pretending the camera lens is itself made of stained glass.

Wake Up Dead Man doesn’t bring the same humor or the same intricate mystery as the earlier films, but it feels like the most substantial, most thought-provoking of the bunch. At one point Jud and Blanc discuss how so much of religion is about storytelling. For Blanc it’s an incrimination of the whole bloody thing, but Jud’s willing to own it. Because at the end of the day what Jud understands, and Johnson with him, is that the exact same thing is true for solving a murder. After all, Blanc revels in few things as much as laying bare all the sordid motives and machinations of his suspects, deftly revealing the solution as the showman that he’s inclined to be. Here in this mystery, putting the puzzle pieces together is secondary to that, to telling the story. As Jud gently responds to Blanc, the question is, do those stories resonate?