Sentimental Value Offers a Home to Our Wounds and Insecurities

Imagine your house. Not the one you live in right now, but the one you grew up in. Your childhood home. If that’s the very house you still live in, all the better. Envision its windows, pick one and picture the view that it framed outside. Now imagine the many decades that house has stood, the various people—your family, perhaps other families—that have lived there. What sort of scenes were held in that window frame, what dramas or acts of play or episodes of heartbreak? And what if, instead, you were looking through that window from the outside? What scenes would you bear witness to taking place inside the house, what romances or tragedies would be staged within?

Just like every other aspect of our childhood, the homes we grew up in shape us. A home is not merely a structure, but a guide and a companion, in its own way. It encourages a certain way of living. It also houses our griefs, our pains; a home absorbs those things and is marked by them as much as it becomes marked by crayons on a wall. If the former are less physical, they are no less real in our understanding of our homes.

These two dynamics provide the foundation for Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value: How a home changes shape over time, and how it changes the shape of its residents’ lives. The Oslo house in question has belonged to the Borg family for at least five generations. The red wood of its frame received the touches of young girls and boys who became women and men, some mothers and fathers. While the garden’s large bushes would have restricted the gaze of passersby, the house witnessed deaths of some, the births of others. It floated secrets through its walls to the ears of attentive eavesdroppers. And it aged, a glaring crack revealing the flaws that time and the world inevitably inflict upon all bodies.

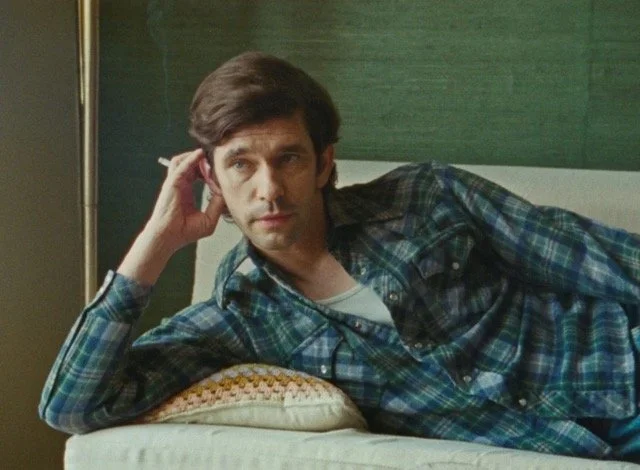

Trier’s story centers on two generations of the Borg family. Gustav Borg (Stellan Skarsgård) is the current patriarch, though he mostly eschewed his duties after leaving his wife and daughters years earlier. But now that their mother has died, Gustav returns and aims to revive his relationship with his daughters Nora (Renate Reinsve) and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas). Herself a wife and the mother of a young boy, Erik (Øyvind Hesjedal Loven), Agnes is more receptive to her father, more forgiving of the past; but Nora still harbors a lot of pain, keeping Gustav at significant distance. Her relationship with her father is also complicated by their shared pursuits—Gustav is an internationally renowned film director, and Nora has become a skilled actress on stage and television.

When Gustav arrives not just with condolences but with a new movie script that he wrote with Nora in mind, all the comforts and the wounds of the past rise up once more. As he puts it, she’s the only one who can possibly play the role. Reeling from the thought of being stuck working with her father, Nora rebuffs him. An impulse, albeit an honest one, but it only results in a new sort of wound when Gustav decides to go ahead with American actress Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning). So much for Nora being the only person who could do it. Rachel thus enters this familial landmine appropriately ignorant and cautious.

Trier and his crew, including co-writer Eskil Vogt, editor Olivier Bugge Coutté, and cinematographer Kasper Tuxen, bring a calm yet arresting eye to this family and their history. While these three are the central characters, the film also opens up to encompass the earlier Borg generations, the lives that came and went in ways mundane and tragic, alike. It creates a richly textured fabric of history, family, and personality that all resides within the walls of this home. The garden may change, the interior be renovated, but the events and people that were held within this place have left their mark. On a minute level, the visuals and dialogue each seem simple enough, but as the scenes weave together, it depicts a grand and complex humanity. There’s also a dark wit strewn throughout: leave it to a European arthouse director to give his grandson a Michael Haneke film for his ninth birthday.

Reinsve (who also starred in Trier’s The Worst Person in the World) is an actress of remarkably delicate expressiveness. Not “delicate” in the sense of weak or fragile—she presents a refreshing boldness of emotion—but in the sense that even the smallest reaction reflects the turmoil within Nora. Her vitality is equaled by Skarsgård, who exudes Gustav’s blundering overconfidence along with his emotional frailty. Lilleaas, too, is excellent as the younger sister who sits slightly farther from the center of conflict, though carries her own frustrations as she navigates Nora and Gustav. Everyone wears their insecurities and wounds so openly, and seeks to harbor them or expel them in such a truthful manner. Each generation confronts its own artistic, familial, and romantic disappointments, and each generation responds to those pains in its own way.

Sentimental Value is carefully attuned to those pains and the way they change over time. In fact the passage of time, itself, hurts. We hurt those we love, those we have failed so many times. History hurts, with its waves of injustice and tyranny. And how easy it is for the flourishing of others to feel like fresh wounds in the face of our envies and unfulfilled longings. Yet for all that, we still choose to hold so many things dear. Our family, our loves, our homes, our memories. The marks made on our homes by time and our own lives are equally marks made on our lives by the places we’ve lived and the people we’ve lived with along the way. That’s what Sentimental Value gets at, and I am fairly well staggered by its emotional heft and care.