Peter Hujar’s Day Is a Sensational Work of Recreation

How do you fill a day?

In 1974, the writer Linda Rosenkrantz met up with her friend Peter Hujar to work on a new project she’d envisioned. Both Rosenkrantz and the photographer Hujar were in New York City’s art circles at the time, crossing paths with figures like Fran Leibowitz, Susan Sontag, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. Rosenkrantz’s idea was to interview her friends about what they did during the course of a single day. Nothing spectacular, nothing fictionalized, just the straightforward events of a day. The recordings Rosenkrantz made of her conversations were lost, but a transcript of her time with Hujar was eventually published as a book in 2021.

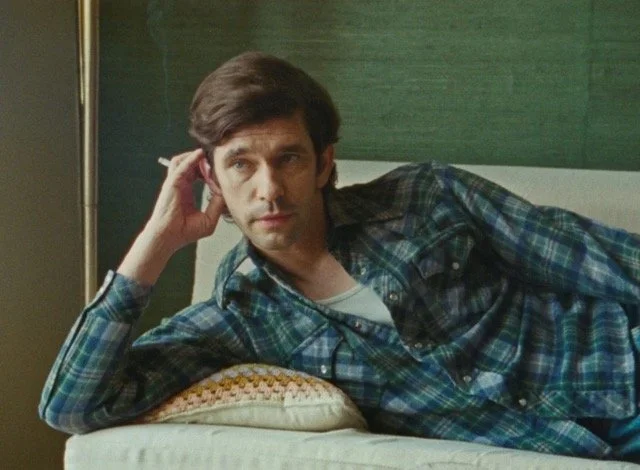

Peter Hujar’s Day, directed by Ira Sachs, is an adaptation of the book (with the same title). It takes place in a single apartment, on a single day, as Hujar (Ben Wishaw) recounts the events of the previous day to Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall). The movie is quotidian, and unapologetically so. It is also grand, and undeniably so.

For anyone unfamiliar with Hujar’s work or Ronsenkrantz’s, including myself, the first draw for Peter Hujar’s Day is likely the occasion to revel in proficient acting. The power of a film situated inescapably within a conversation between two people is tethered to their performances; more than simply being anchors, Wishaw and Hall’s performances propel the movie to a power that exceeds its simple nature. Wishaw’s role is the one on center stage and is a tricky one, balancing Hujar’s verbal intonation and habits of speech with physical embodiment and gestures. Yet the actor appears so relaxed that every movement and response seems like the most natural act. His poise masks the difficulty of his task—he appears so eased that, despite Wishaw’s familiarity, it’s easy to forget he’s acting. You get such a feel of Hujar’s energy from Wishaw’s performance. But is it Hujar’s energy or Wishaw’s energy? The film doesn’t contend that they’re the same but that the difference doesn’t matter.

While it requires less physical and verbal contortions, Hall has a challenging role, herself. Linda is primarily a listener—she is not an audience stand-in, but she has only sparse dialogue, meaning that Hall has to form Linda’s distinct personhood through the forms of physical relationship. She moves comfortably around Wishaw’s Peter, accommodating his movements and engaging in the familiar touch of close friends. Sometimes that means not visibly responding to Wishaw’s lines—we don’t gesture after everything someone says, especially someone we know well. Hall does a tremendous job, even if Peter is the memorable character from the film.

Despite its simplicity, Peter Hujar’s Day hides a bit of complexity. How close does this film stand to reality? This is not a documentary; it’s not quite a biopic. It’s an adaptation of a transcript of a day. Yet even a recorded conversation bears some element of the fictional within. As Peter recounts the events of the previous morning, he editorializes one part: “I’ll tell you the other version.” He catches himself distorting the events of the day to present them a little closer to how he wanted them to occur. Art is the realm of invention, of making things up. In a way, the same is true of memory. This is not a tension for the movie; rather, it’s the raison d'être.

The origin of Peter Hujar’s Day invokes a hesitant question: Why make a movie of this? Sachs’ answer is to create an immersive and distinctly cinematic world that the audience is warmly invited into. We get to share these private moments with Linda and Peter, but we also get to step into the New York City of the mid 70s. Not the real New York, necessarily, but the memory of it. Alex Ashe’s photography is tactile and magnificent, even before the magic hour sky bursts in sensational purples and oranges. Smart, complicated images punctuate the mundanity, as when Linda goes down to the kitchen to prepare some food. The camera captures her shoulders and head above the partition, and Peter eventually enters the frame on the floor above, so that only his legs and the bottom half of his torso is shown. In another instance, the camera pans from Peter’s face to Linda’s; after a moment, the focus switches and Linda’s face is blurred but held for a pause before the frame slowly shifts back to Peter in focus.

The word incarnate came to mind at times while watching the movie. Perhaps that’s the answer to why turn this into a movie. A published interview can give a sense of the personality. But Hall and Wishaw’s performances incarnate these artists—Hujar and Rosenkrantz are before us in all their immediacy. The visual world that Sachs and Ashe craft is also a work of incarnation, but for a time that has passed, a place that has changed. Peter Hujar’s Day is an act of cinematic recreation in the deepest sense. It is quotidian, yes. But it also feels irreplaceable.