Marty Supreme: American Narcissus

After the breakout success of Uncut Gems, the Safdie brothers parted ways (at least for now) and created their own films. Two paths diverged in a forest: Benny’s The Smashing Machine took on a more tried and true approach to a character study while tackling what is perhaps the ur-cinematic sport, boxing; Josh, meanwhile, turned to the unexpected sport of table tennis—no one’s idea of blockbuster thrills—but stuck to their trademark speed and stress. Anyone who reflexively clawed their nails into the couch or theater seat armrest watching Adam Sandler’s Howard Ratner gamble his way toward cataclysm in Uncut Gems will have a pretty good sense of what to expect with Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme. Buckle in for another nerve-fraying ride.

There’s certainly a lot of Howard Ratner in Timothée Chalamet’s Marty. He’s driven to a maniacal degree to achieve his goals, but his aspirations far exceed his actual ability to get there. Still, he’ll pursue that dream at any cost, constantly pushing those costs onto the shoulders of the people around him. He’s far more charismatic than Howard, to be sure, but he’s just as infuriating and exhausting. Marty’s never met a problem he can’t refract into five new problems. Meet your new American Narcissus.

The year is 1952, and the world is slowly recovering from the devastation of World War II as industries reshape peacetime and people everywhere wrestle with the legacy of ethnic animus toward those who were their enemies less than a decade ago. And, of course, any preexisting prejudices remain as spiteful as ever. But culture is shifting, and the lines of business, society, and the increasingly global economy are being redrawn. There’s certainly no avoiding either the changing times or the cultural boundaries in New York City, especially for a young Jewish man trying to chase his dream. Call it what you want, in fact: dream, hunger, lust, fixation, fetishization. While there are many things you could label Marty—a hustler, a go-getter, an egomaniac—you could also just see him as pure, all-encompassing appetite. Thus he tries his damndest to bed a movie star (Gwyneth Paltrow’s Kay Stone) whose 1930s fame has now dissolved into a “hey, isn’t that that actress?” level of notoriety. Thus Marty orders the most expensive things on a menu, as if that is the same thing as having taste. Thus he grabs and grabs at any cash in view, no matter how obviously flimsy his schemes may be. He’s described with succinct aptitude as “one entitled American.”

Marty’s biggest goal is to be the number one ranked ping pong player in the world. In fact, he’s already number one in his own mind; he just needs to convince the rest of the world. But it’s that piece that Marty has particular trouble with: the world. He’s strapped for cash and his family and friends are tired of his false promises. He’s gotten Rachel (Odessa A’zion) pregnant, but he dismisses any responsibility for the child, calling it a “biological impossibility” that he could be the father (despite his refusal to wear a condom). When he actually has to interact with the world beyond his city, things somehow go from bad to worse. Marty makes light of the atrocities and suffering that occurred in the Holocaust and World War II, and he belittles the skill of his main opponent, Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi). You see, Marty’s not just one entitled American. In fact, he’s the personification of American exceptionalism combined with postwar striving. Of course he’s the best, of course destiny is waiting for him to claim it, of course all of these problems are just distractions keeping him from his deserved glory.

If spending two-plus hours watching as an American man, insistent on his rightful dominance and deluded by a false image of his own charisma, acts with (imagined) impunity as he foists the destructive results of his actions onto everyone around him, blind to everything except his quest for glory sounds like a way you’d rather not spend your time—well, that’s understandable. But as with Uncut Gems and Good Time before it, Marty Supreme builds a stressful jack-in-the-box around such an insufferable protagonist. The tension builds and builds and builds as the story cranks forward, and you’re just bracing for the catastrophe to bust out. Safdie is once again working with co-writer Ronald Bronstein, and together they craft a plot as surprisingly (and uncomfortably) funny as it is unpredictable. Each individual scene is impeccably inscribed with anxiety and shock—you know things are headed in a bad direction, but it’s impossible to guess what that destination is. There’s something missing, however, when the full arc is considered. In the previous films, every ratcheting of the plot was propelled by the character’s willful choices: they were crafting a Rube Goldberg machine of their own eventual downfall. Marty Supreme isn’t nearly as tightly scripted. Various events and plot threads instead happen at random to Marty, and, while he certainly makes bad choices in reaction, there’s an arbitrariness at play that takes away some of the investment in his path. It keeps Marty Supreme from the greatness that Uncut Gems and Good Time (in my opinion, still the best of the bunch) achieved.

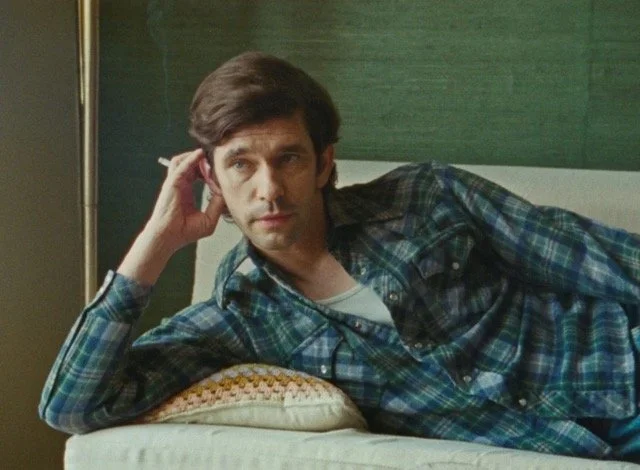

The weight of the film is squarely upon Chalamet’s shoulders, and he responds with his most muscular performance to date. That’s not to say it’s quite his best, but it’s nonetheless impressive, putting a broader scope of his talents on full display than Dune or even A Complete Unknown. As Marty, Chalamet brings an unbelievable amount of energy to the film, never slowing down for a millisecond, demanding that everyone—the audience included—keep up. It’s exactly what the film calls for, and Marty has just enough charm to make us interested, even if we know we shouldn’t be. Chalamet’s roles often land somewhere between boyish and impish, and Marty Supreme superimposes those qualities to really sell this character who appears impervious to consequences and is just so impossibly self-assured. Few would be as convincing delivering the ironic confidence when Marty declares himself “the chosen one” “uniquely positioned” to be the next star of table tennis.

Marty Supreme knows its hero is so exhausting, and that’s where its potent critique lies. At one point Marty declares that “everything in my life is falling apart, but I’ll figure it out.” His exceptionalism applies even to his own suffering, apparently. In honesty it’s a pretty familiar impulse in our culture. It’s simply a Navy Strength individualism that Marty’s drunk on, no different in nature from the more commonplace refusal to help others or accept help from others that our grand American myths persistently laud. For this brand of American individualism, it’s bootstraps all the way down. It is indeed tiresome, so the call is to reject it in the real world and not merely in fictional characters.

For all the stress and bad decisions of his characters, Josh Safdie still has a caring gaze. In this aspect as in his movie’s narrative anxiety, Safdie seems an inheritor of Martin Scorsese’s ideals. (In fact, I could easily see Safdie proclaiming “Marty supreme” as his view of cinematic history.) But there’s also been a connection to the films of the Dardenne brothers, and that only becomes more pronounced in Marty Supreme. I can’t describe what I mean in detail without tripping into spoilers, but the insertion of a particular pane of glass in the final scene, combined with Marty’s direct gaze, locks this in for me. And hey, Scorsese and the Dardennes are some of the greatest filmmakers of the past fifty years. If Safdie looks at their legacy as a mantle he wants to carry forward, I’m thrilled to follow along with many films to come. Even if that means chewing my nails from stress.