Distress, Dread, and Vulcanizadora

Joel Potrykus’ Vulcanizadora opens with heavy metal blaring as two men walk side by side through the woods. But when the music suddenly cuts out, the next instant is a laugh, a deflation of the manufactured intensity of the metal. In hindsight, this moment is a necessity, a small moment of levity to cling to in a film that will only grow darker and bleaker. Vulcanizadora boasts an incredibly strong artistic voice and style for its small budget. It achieves all that it seeks to accomplish—which just might make it the feel-bad movie of 2025.

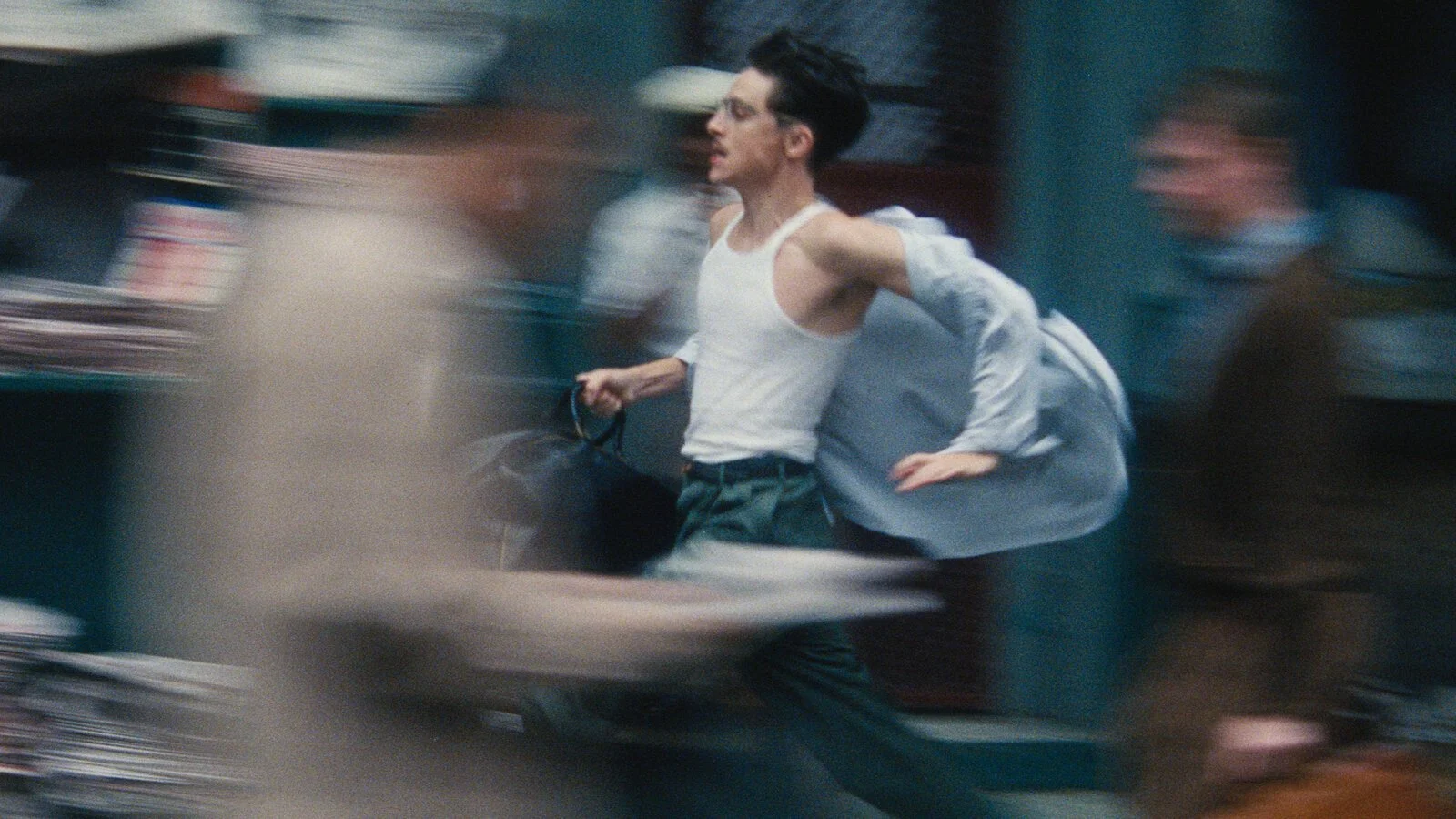

Derek Skiba and Marty Jackitansky (played by Potrykus and Joshua Burge) are on a camping trip, and we meet them as they begin their walk through the Michigan forest towards one of the Great Lakes. They’re old friends mismatched in their outdoors preparedness; Derek, clad in hiking pants and boots, carries a pack with supplies, while Marty stumbles around in jeans with almost nothing else for the excursion. Derek ribs Marty for this decision, but his confidence is a bit overbaked—he repeatedly leads Marty in the wrong direction and makes a fool of himself as he attempts a fire.

They’re also of different strokes in their demeanor: Derek never shuts up, as if he has to verbally process every single thought to himself. Potrykus has a relaxed madness to his performance, talking breathlessly about chips about fireworks about fires about other people they know about how much Marty’s gonna love this next bit about his son Jeremy about samurai about anything at all. Burge plays Marty with a shivering discomfort that covers over annoyance, or perhaps a boiling rage. At first Marty seems uncertain, but over time he reveals himself to be contorted by emotion. Both performers are affecting in their moments to shine, though the script tends to only manage one at a time in terms of depth.

Despite their differences, Marty and Derek are united in their mission and in their disposition toward life. These are two men who never passed adolescence. They chop at trees with sticks as if swordsmen, they try to blow up Gatorade bottles with firecrackers, and they glancingly note the collapse of their adult responsibilities. It’s as though their maturity decided to play hooky around age twelve, and society has apparently tired of them. The goal of this trip is too obvious and too present for these men to ever reference it, but it’s opaque to us. Along the way there are signs of danger. Subtle at first, but they accumulate, suffusing the forest with an apprehensive atmosphere of despair. Discomfort heats up into distress, eventually boiling over into dread. Wherever this trip is leading, there’s no good destination for Marty and Derek. It’s clear that, whatever occurs, it can only result in tragedy.

Potrykus builds up the dread meticulously (culminating in one of the most distressing scenes I’ve witnessed in a long time, in which Portykus refuses to cut away to provide any relief). The filmmaking is mostly simple, the camera jumping across moments of dialogue, the camera fixing close to either character. We read their faces clearly, though we don’t always understand the underlying emotions. Diegetic noises are heightened, making potato chip bags and lapping waves loud enough to compete with Derek’s motormouth. The soundtrack alternates between heavy metal and (unexpectedly) opera: both bombastic, both explosive with emotions that perhaps could never be spoken. Derek and Marty struggle to express themselves, but the overwrought music communicates their internal tumult.

There’s a lot of Old Joy in Vulcanizadora’s DNA—it almost reads like the bleakest possible version of Kelly Reichardt’s melancholy interrogation of male friendships. There’s even a hint of the Dardennes’ L’enfant, as each film observes characters hoping for some sense of reconciliation amid a society that would rather dismiss them. And maybe (just maybe) a touch of The 400 Blows. It’s a renowned cinematic pedigree for a film that, at first glance, appears to be so off-putting.

All of this is to say that, while Vulcanizadora is not likely a film I’ll choose to watch again, it knows exactly what it’s doing. It’s an assured and troubling feature. And despite the discomfort and sorrow that it conjures, I’m far more interested in its provocations than in the meager attempts at boundary pushing that bigger directors such as Ari Aster and Yorgos Lanthimos have swung for this year. Vulcanizadora avoids easy answers to its questions, but it clearly has a substance to its provocation.