The Didactic Apocalypse of Godard’s Weekend

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film Weekend opens with a title card that reads “A film adrift in the cosmos.” A few seconds later, a second title card flashes on screen: “A film found in the dump.” Weekend seems intent on—or at least aware of the inevitability of—opening itself up to quite divergent readings. That awareness is foundational; this is a film marinated in the ideas of post-structuralism. Derrida’s influence was rising rapidly, and Roland Barthes’ essay “The Death of the Author” was first published in the same year.

The duality of these opening statements serve as a good summation of Barthes’ idea: The film leaves it up to the audience to determine which title card is a more apt description. Roger Ebert loved it. Pauline Kael spoke of its immense power and mysticism, but stumbled a bit at Godard’s “agitprop preaching.” Unfortunately I am inclined toward the second option. It’s undeniable that there is a vicious vitality to Weekend, one that breaks through effectively in disparate moments. But it also belabors the point as it repeats and devolves into showier forms of vulgarity.

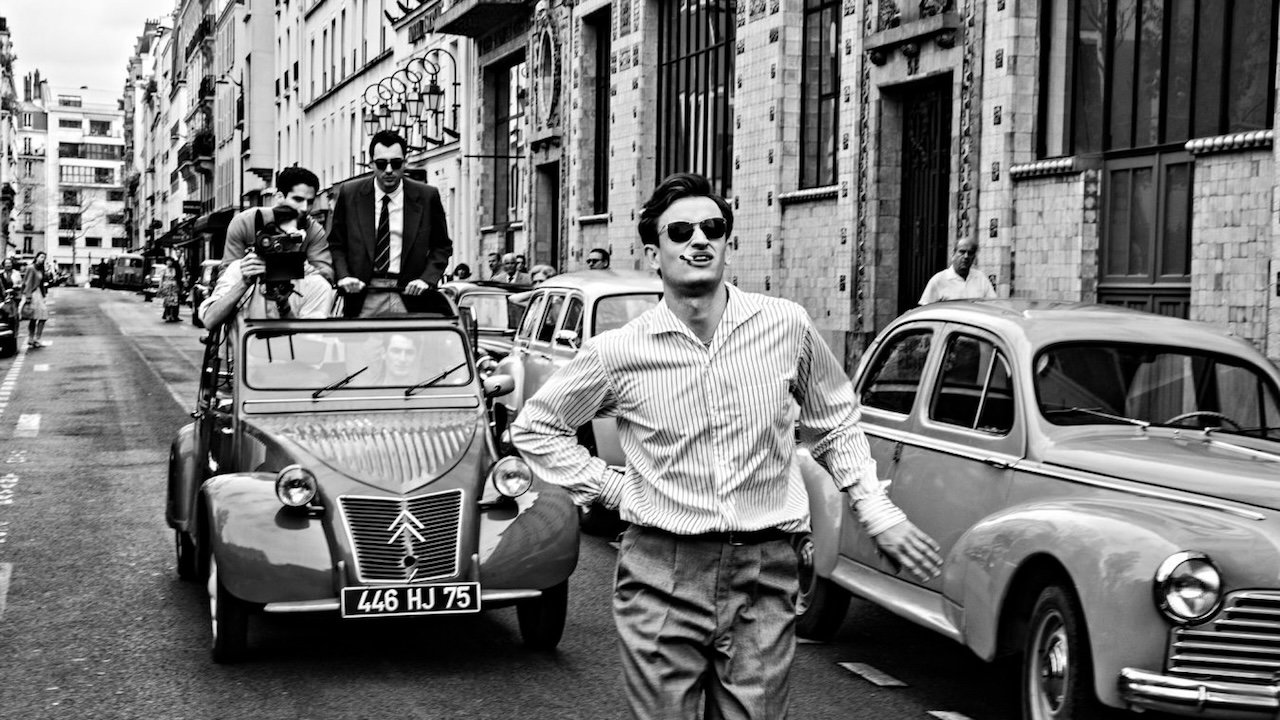

With Weekend, Godard made a scattershot film that has a didactic (if deconstructive) aim, its anger spreading out in a variety of directions. Adherence to narrative is only cursory here, which allows Godard to spin his vignettes in all directions against French and Western society. A married couple drives out to the countryside to meet the woman’s parents for the weekend with the goal of securing a place in her father’s will. (They speak openly and flatly about their wish for both parents to die.) They are, however, waylaid by every possible annoyance. An endless traffic jam (which forms the film’s most famous scene and provides a substantial portion of its wit), a car crash, a highway robber, another car crash, historical figures that refuse to help them, more car crashes, and revolutionaries.

In place of narrative momentum, the movie consists at every moment of fury. And, hey, when the seething frenzy of a decadent society is your subject, why not open with road rage and car horns? Before they’ve even hit the road, we’re witness to two separate fights in parking lots. The dominant score of the film is achieved by car horn, the ever at-hand tool of modern disapproval. The violence intensifies quickly, leading from arguments and horns to fistfights and aimed weapons, eventually ending in outright murder, the killing of animals, and a hint of cannibalism. Weekend is a wildly misanthropic film, one that sees humanity as an endless cacophony. The dialogue of the protagonists externalizes the vilest of human prejudices and narcissism—they’re in a rush and they don’t care who’s harmed as they try to get there. There’s no need for zombies in Godard’s vision of apocalypse.

Godard is out to burn the trivial self-satisfaction of 1960s French culture, and his critique finds its target. But the film begins to fray as mistakes accumulate. The car crashes lose their potency after about the fifth splayed body (although the woman lamenting her Hermès handbag as a body burns nearby sparks a pointed, bitter laugh). Godard makes the poor choice of referencing a (much better) Buñuel film. As society fully comes apart at the seams, the vulgarity and hatred loses its subversive value and becomes tiresome. Still Godard presses in, just in case you didn’t understand his point.

To add to this, he inserts long stretches of invectives against French colonialism in Algeria and America’s war in Vietnam. Point taken. But Godard’s framing of this scene and others like it are, unfortunately, the film at its most forgettable. He could either rest on the strength of his symbolism or express his points directly and with vigor. He attempts both; he weakens both.

Godard’s skill is evident, even in the more pained moments. There are quick, crashing edits that frequently jump to title cards. The traffic jam and other sequences are filmed in long takes, hiding intricate choreography that would be otherwise at home in a Jacques Tati film. On an individual level, the scenes are visually enthralling. Even with all those techniques on display, though, Weekend evokes nothing more than an overlong essay by an insufferable sophomore who just discovered post-structuralism.