Highest 2 Lowest Lands Somewhere in the Middle

Spike Lee is a generational filmmaker whose career, littered with modern touchstones, searing critiques, and occasional misses, has earned him the leeway to pursue any form of project. Nearly four decades on from She’s Gotta Have It, Lee is still delivering strong films such as BlacKkKlansman and Da 5 Bloods. So why not reach back in cinematic history and sculpt something new out of one of the greatest films of all time, made by one of the greatest filmmakers? Spike’s earned our trust, is what I’m saying.

His latest film, Highest 2 Lowest is a reinterpretation of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low—perhaps Kurosawa’s greatest film, though rarely a viewer’s first experience with the director. While both films adapted from Ed McBain’s novel King’s Ransom, Lee’s debt to High and Low is explicit from the title. Both films foreground wealthy, ambitious men thrown into a moral dilemma; they both center around kidnapping, mistaken identity, and corporate intrigue; and they both unfold as a diptych, each half carrying an entirely unique sensibility.

David King’s world is the city and its sounds. As a man who loves discovering music and carries a sharp business sense, King (Denzel Washington) has built his Stackin’ Hits Records into a stronghold in the industry. But time changes everything, and heavy lies the head that wears the crown. King is weary, his company’s dominance over the industry is slipping—maybe precarious—and it might just be time to sell. On the other hand, maybe David just needs to find inspiration again and take ownership back. As he says early in the film, “You gotta be a little crazy in this world to get what you want.”

Before such business moves are played out, however, David’s world is pierced when he receives a call from a kidnapper demanding a ransom for his son, Trey (Aubrey Joseph). He can afford the ransom, but it would cost him his dreams of rebuilding his music empire. It’s a simple enough plot, unremarkable except for the real crux: the kidnapper actually snatched the wrong kid. It’s not Trey but Kyle (Elijah Wright)—the son of Paul (Jeffrey Wright), David’s chauffeur—who’s been kidnapped, but the perpetrator is undeterred: David King will pay the ransom, or Kyle gets killed.

This is the dilemma that Lee (and Kurosawa before him) is intrigued by. The first half of the film consists of set up and the ensuing moral quandary David must stare down. Where High and Low’s power came from the unstated, Lee’s film is often sharply direct. His trademark didacticism remains: here, he uses it to consider the changing mores of music genres and artistic fame, but he also brings forward the topic of the Ebony Alert system to help locate missing Black men, women, and youth. Though recently established in California, Ebony Alerts aren’t an available tool in New York, frustrating the Kings’ search attempts. There are also tangents to be followed about the exploitation of Black music for corporate profit. (Highest 2 Lowest is the second popular film this year to address this theme, though it does so with less layered richness than Ryan Coogler’s Sinners.)

At its heart, though, this was always a morality play. What will a rich man do when faced with a choice between his ambition and the life of an employee’s son? There’s a stylistic gloss that adorns much of the film right from the opening. The camera angles show glimmering shots of New York and David’s Brooklyn apartment, in particular, with a filmic lust for wealth and status—a lust that Lee is already subverting. Even as we’re impressed by this home, the sunlight on the windows reflects the unknown world of the city, as if David’s wealth is resisting, repelling the very place that has made him. As the kidnapping confounds David’s security, Highest 2 Lowest becomes a consideration of how wealth corrodes integrity and whether the latter can survive in a world shaped by the former.

It comes as no surprise that Denzel carries the film, David’s hesitation and charm and bravado and awkwardness are all instantiated through Denzel’s subtle, physical performance. Few actors are more captivating while listening, more curious in a simple glance as Denzel is, and every film we get with him at its center is a gift in itself. The performances around him, however, are shakier. Jeffrey Wright (acting alongside his son, Elijah) is one of the few who can hold an extended scene with Denzel, and Paul is played with consideration. He’s both quiet and noticeably tense, calming himself with prayers and near liturgical reminders of his and David’s belovedness. Ilfenesh Hadera as Pam, David’s wife, and the central trio of cops investigating the case are fine, if notably flatter.

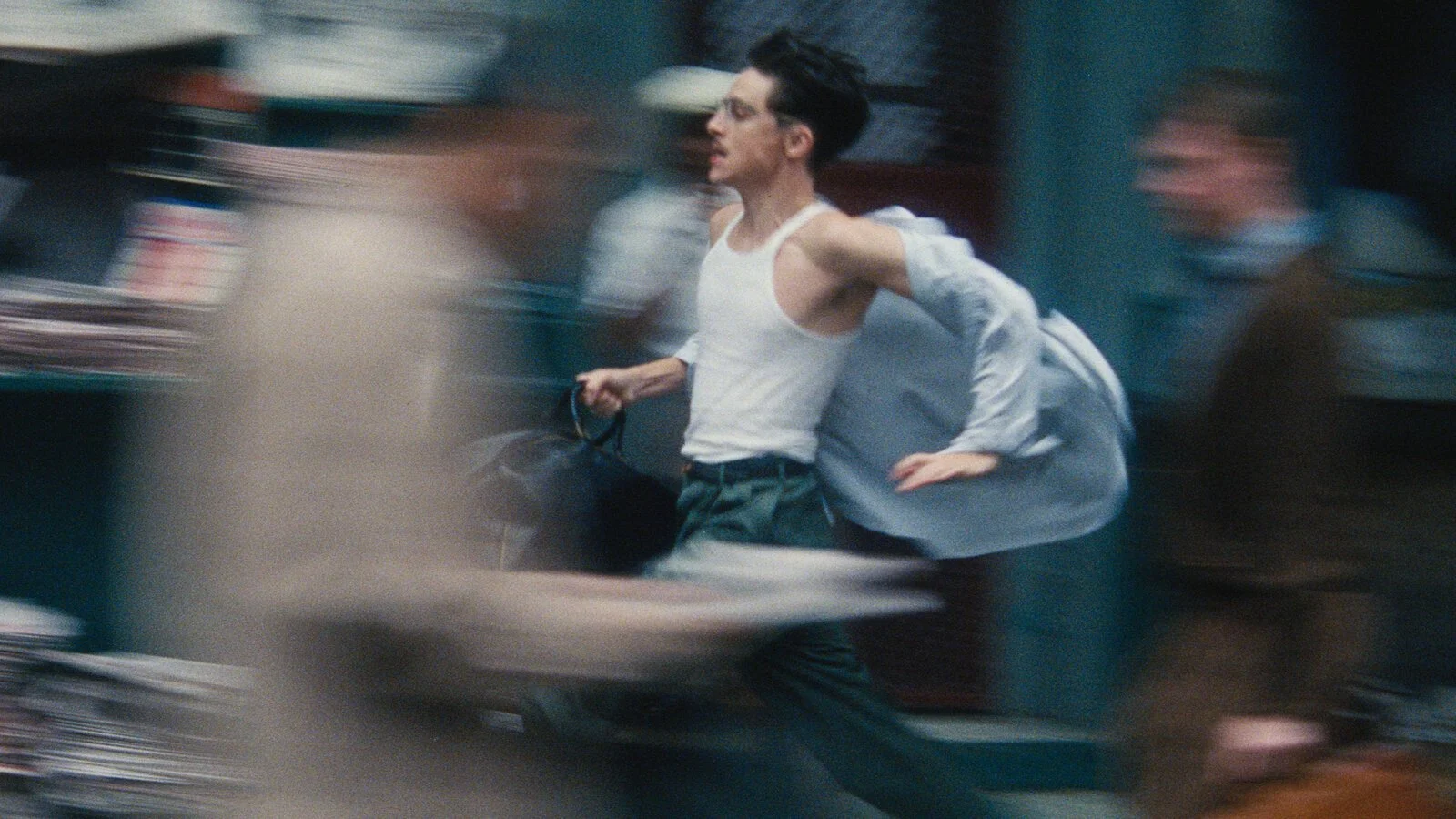

Once David goes to deliver the money, the visual gloss is shattered, suddenly jostling the film with energy. Grainy film stock signals David’s return to the real city that he would have known decades ago. (The texture, combined with the subway setting, hearkens further back to central New York films like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.) The set piece is Lee’s finest work here, integrating a Puerto Rican celebration and fans on their way to a Yankees’ game. It’s vibrant and cultural, progressing with enough breathing room to emphasize that this is the New York Lee loves and wants to express. It’s a far cry from David’s penthouse, but it’s filled with much sweeter sounds.

The film maintains its momentum from there. The studio scene late in the movie is an immaculate showcase of script and performance, both of the performers suddenly reaching a higher gear. It’s electric, but it feels as if Denzel has been patiently waiting for material honed enough for his skill. It makes one wish the script was as sharp through the entire film.

There’s less tension, less emotional pain, in the first half than that of Kurosawa’s masterpiece, but once David hops on the subway, it opens up into something more invigorating and distinct. But even once Highest 2 Lowest loses its gloss, it all goes down a little smoother than it should. For such a wrenching moral dilemma, the resolution comes too directly, diluting a fuller catharsis. Highest 2 Lowest is a fun movie whose tangents are often more interesting than the core of its substance. It doesn’t reach the highs of BlacKkKlansman or Inside Man, but Denzel’s performance and Lee’s setpieces are worth the price of admission and the ambitious reach to reimagine Kurosawa’s film.