Cloud Casts a Shadow over the Digital Marketplace

In 2001’s Pulse, director Kiyoshi Kurosawa investigated the tension between the burgeoning internet’s promise of connection and its atomizing influence. As people reached out into the digital void, they became more isolated, and the response they received became their doom. Pulse envisioned a spiritual loneliness in its characters juxtaposed with a spiritual evil as a symbol for the internet’s power. In the decades since, our lives have become increasingly—overwhelmingly—integrated into and shaped by the internet. The cultural change necessitates a different vision of the digital landscape—a vision that Kurosawa offers in Cloud.

Ryōsuke Yoshii (Masaki Suda) doesn’t appear to be entirely isolated. After all, he has a stable job and a girlfriend, Akiko (Kotone Furukawa). But this side of his life is sequestered from his digital life, where he’s better known as Ratel, an online reseller of items that vary from medical devices to knockoff handbags. Like those handbags, his practices aren’t on the up-and-up: he buys up all the stock he can at a cut rate to create an artificial demand, then sells each item far above the market value. Perhaps the best thing that can be said here is simply that his strategy works, though it begins to create a subcommunity of people who have been victimized by Ratel’s immorality.

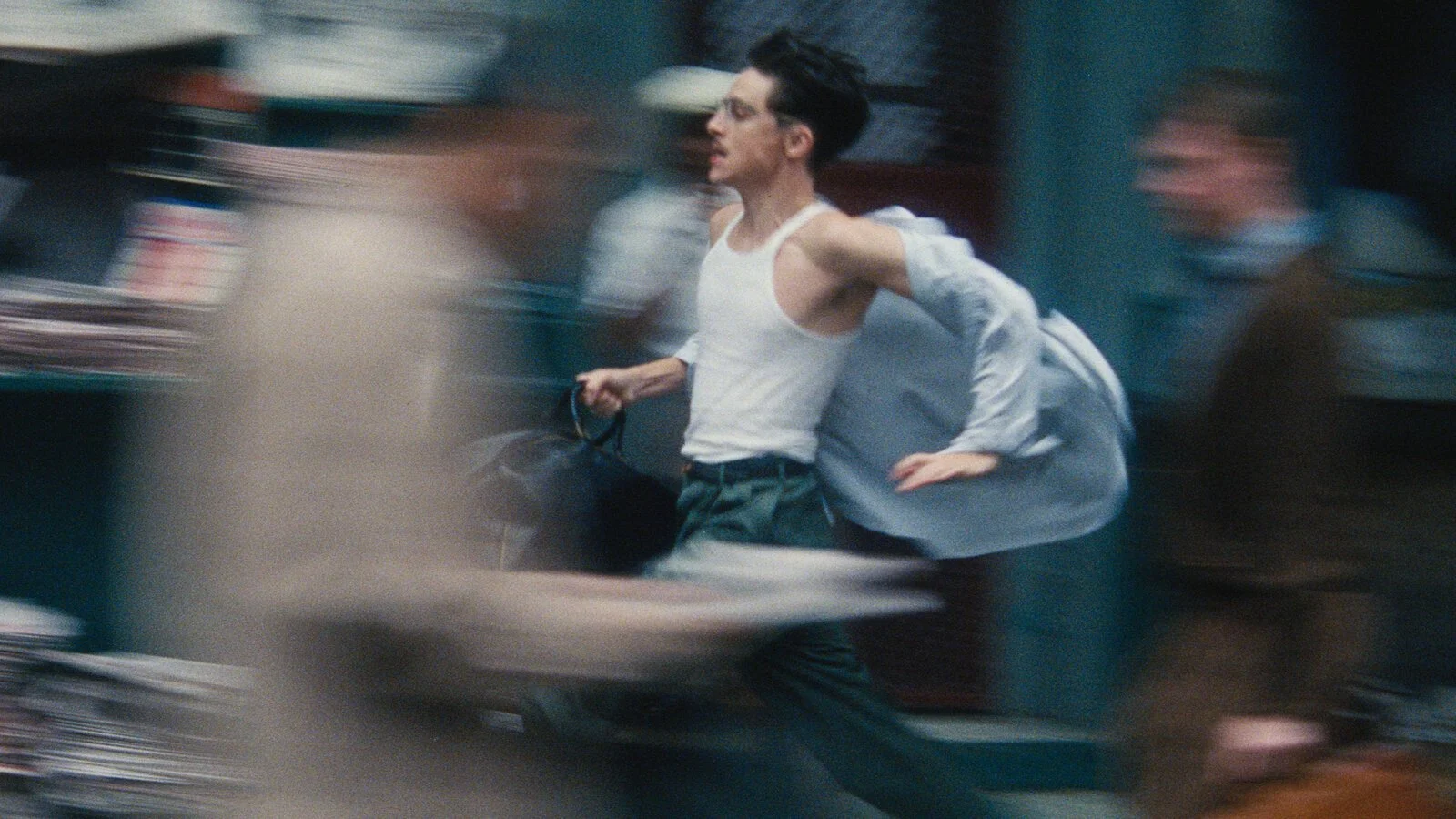

Morality is hardly a category for Yoshii; he’s focused on blunt economics. He’s asked at one point by his assistant, Sano (Daiken Okudaira), “Being real or fake doesn’t matter?” “It doesn’t,” he replies. But there is a real Yoshii behind the facade of Ratel, and those angry commenters start trying to track him down. After a busted window and a knock on his door, Yoshii moves with Akiko to a large house in the countryside, but it only delays the mob that comes for him. The social commentary devolves into a home invasion thriller, which transforms into an all out war.

Despite decades of filmmaking and many strong films, Kurosawa is relatively undercelebrated (at least in the West). While Cloud isn’t his best work, his skill is consistent and apparent, particularly when crafting an atmosphere of cold isolation and fear. Much of Cloud is perceived in simple, still frames centering on characters. But these frames are frequently arranged by exacting camera pans and tracks. The style is more dynamic than it feels—the images may strike as mundane or realistic, but there’s an undercurrent of energy that unnerves over time. Or consider the blocking of a scene where Muraoka (Masataka Kubota), an old schoolmate, tries to hook Yoshii into investing in a new auction site. What seems common on the surface actually requires great planning, conveying the interpersonal dynamics of this verbal game. When the violence arrives, it’s vicious. Faces crunch under fists, and gunshots deafeningly reverberate through an industrial warehouse. Kurosawa weaponizes negative space, freighting any geography in the frame behind the character with anxiety.

Cloud depicts an evil altogether more mundane than that of Pulse. As the internet pervaded the lives of its users, it could no longer be considered a haunting. The alienation of Pulse has affected everyone; the atomization is felt everywhere. Combined with the raw cynicism of market economics, the atomization frames everything as competition. It’s all about perceived value and selling price. What is true for anime figurines and medical devices is also true for loyalty and for mercy. (For his drive and resourcefulness at work, Yoshi is told that he’s “cut out to be a leader,” but those very traits also create enemies.) His isolation is total. People are against him, but he has no idea who. Every piece of information someone learns about him is as ominous as a knock on his door in the middle of the night.

He’s not the only one affected, though. The callousness of the digital market extends its reach, so that Yoshii’s victims no longer care about their own victims. Here, the evil Kurosawa has in view does share a common thread with Pulse and Cure—the particular invades the social, refusing to be limited to one person, one instance. Kurosawa’s films look at the tendency toward evil that underlies modern society. We like to think we’ve excised evil, or the thirst for violence, far from the psychology of our cultures, but Kurosawa manifests the societal drives (toward profit, toward unleashed rage) into visible forms.

In this sense, and despite the comparative absence of the supernatural, Cloud can be seen to depict the demonic. This evil spirit, however, does not channel itself into ghosts or command individuals through possession; instead, it animates the merciless market economy. It is the demon that whispers in our ears: “Please keep focusing only on making money.”